For now, Kaplan relies on a rule of thumb when looking for new near-miss Johnson solids: “the real, mathematical error inherent in the solid is comparable to the practical error that comes from working with real-world materials and your imperfect hands.” In other words, if you succeed in building an impossible polyhedron-if it’s so close to being possible that you can fudge it-then that polyhedron is a near miss. A hard and fast rule doesn’t make sense in the wobbly real world.

There’s no precise definition of a near miss. But not only does this niggling near-perfection draw the interest of Kaplan and other math enthusiasts today, it is part of a large class of near-miss mathematics. “I sort of set them aside and concentrated on the ones that were valid,” he says. Intent on enumerating the perfect solids, Johnson didn’t give these near misses much attention. If you trimmed the faces, they would fit together exactly, but then they’d no longer be exactly regular. On closer inspection, what had seemed like a square wasn’t quite a square, or one of the faces didn’t quite lie flat. They look tantalizingly open to solution, but ultimately prove impossible.Ī model could appear to fit together, but “if you did some calculations, you could see that it didn’t quite stand up,” he says. “It wasn’t always obvious, when you assembled a bunch of polygons, that what was assembled was a legitimate figure,” Johnson recalls. Once he started to put the sides into place, the shape should click together as a matter of necessity. Because there are relatively few possible polyhedra, he expected that any new ones would quickly reveal themselves. He discovered his shapes by building models from cardboard and rubber bands.

Yet in completing the inventory of polyhedra, Johnson noticed something odd. It is impossible to form any other closed shapes out of regular polygons. And with that, he exhausted all the possibilities, as the Russian mathematician Viktor Zalgaller, then at Leningrad State University, proved a few years later. In 1966 Johnson, then at Michigan State University, found another 92 solids composed only of regular polygons, now called the Johnson solids.

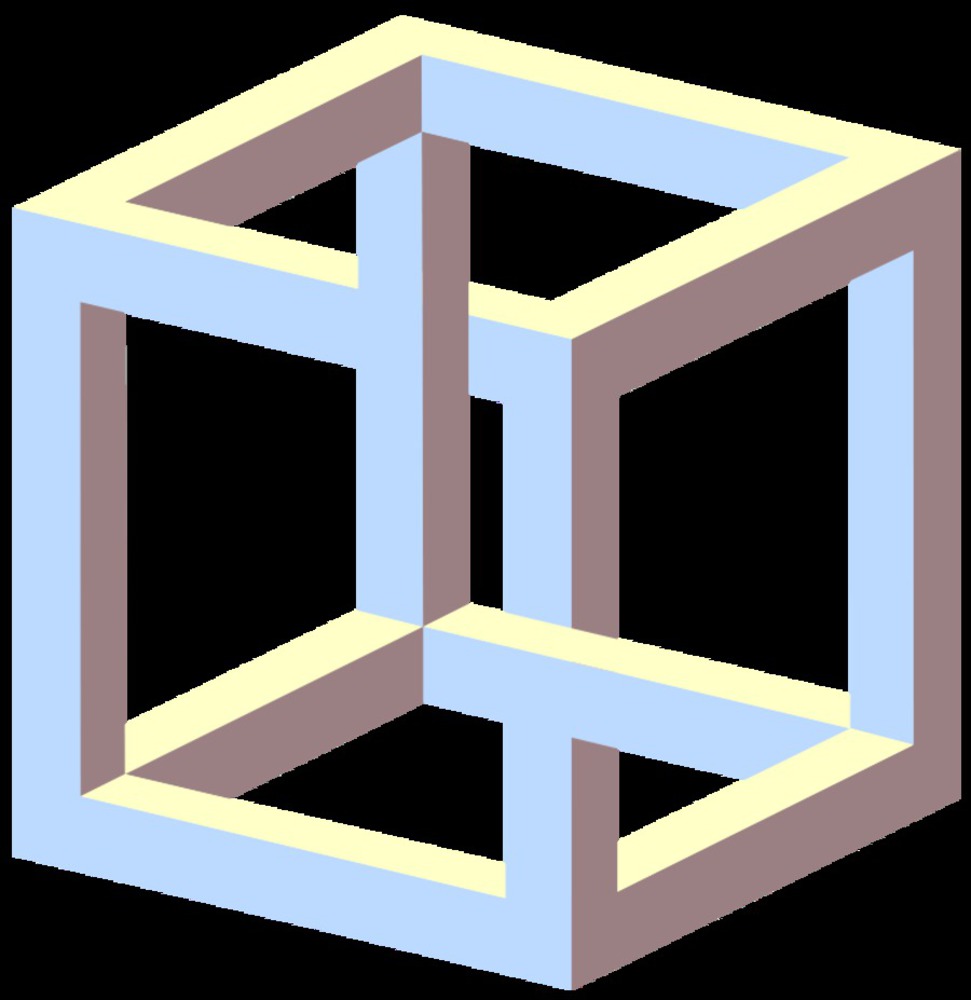

If you mix and match polygons, you can form another 13 shapes from regular polygons that meet the same way at every vertex-the Archimedean solids-as well as prisms (two identical polygons connected by squares) and “anti-prisms” (two identical polygons connected by equilateral triangles). Among the infinite variety of three-dimensional shapes, just five can be constructed out of identical regular polygons: the tetrahedron, cube, octahedron, dodecahedron, and icosahedron. Johnson was working to complete a project started over 2,000 years earlier by Plato: to catalog geometric perfection. It is a new example of an unexpected class of mathematical objects that the American mathematician Norman Johnson stumbled upon in the 1960s. Impossibly real: This shape, which mathematician Craig Kaplan built using paper polygons, is only able to close because of subtle warping of the paper. “The fudge factor that arises just from working in the real world with paper means that things that ought to be impossible actually aren’t,” says Kaplan, a computer scientist at the University of Waterloo in Canada. The sides can warp a little bit, almost imperceptibly. Kaplan’s model works only because of the wiggle room you get when you assemble it with paper. That set of polygons won’t meet at the vertices. It consists of four regular dodecagons (12-sided polygons with all angles and sides the same) and 12 decagons (10-sided), with 28 little gaps in the shape of equilateral triangles. Using stiff paper and transparent tape, Craig Kaplan assembles a beautiful roundish shape that looks like a Buckminster Fuller creation or a fancy new kind of soccer ball.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)